- Home

- Filipacchi, Amanda

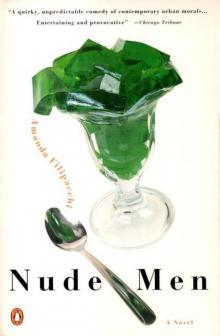

Nude Men Page 15

Nude Men Read online

Page 15

I eat three more mouthfuls using this method, then I place the bitten avocado next to me on the bench, I take out a scrap of paper and my Bic pen, and I make a list of things to do:

1. Have Minou spayed.

2. Kick Charlotte out of my apartment.

3. Get an unlisted phone number.

4. Keep my apartment clean.

5. See more of Laura.

I try to think of other resolutions I might want to add. I want a real list, a juicy, meaty list. Suddenly, a sixth resolution comes to my mind.

6. Ask for a promotion at the magazine.

When I get home, I take out my little ivory elephant and think to it: If you are magic, I make a wish that when I ask for a promotion at work, they will give it to me eagerly. In fact, they will somehow be grateful that I finally asked.

The next morning, when Charlotte has left for work, I get my locks changed. I take all of Charlotte’s belongings and put them in the hallway outside my door. I then call the veterinarian and make an appointment for the following day. And then I call the telephone company to have my number changed. They will change it in three days. Better than never.

I go to work. I will ask them today. How should I act? Strong and confident? Or nice and charming and humble? Asking for a promotion is in itself a strong and confident thing to do, so maybe I should be nice and charming in the execution of that act.

I knock on my superior’s open door.

“Yes?” he says.

“Do you have a minute? I’d like to talk to you,” I ask, smiling.

“Okay.”

I sit across from him and wipe my moist palms on my knees. Annie comes in to arrange some books on the shelves. It disturbs me that she’s here, but my superior pays no attention to her and waits for me to talk, so I begin. “I feel that I have paid my dues,” I tell him. “I’ve filed for a long time. I’ve done a little fact checking, but not much. I was wondering if I could get a promotion.” I glance at Annie. She glances back at me with skepticism; perhaps even contempt; at the very least condescension.

“Really?” asks my boss, looking surprised.

“Yes. Why do you seem surprised?”

“I don’t know. To what position would you like to get promoted?”

“I guess full-time fact checker. At least.”

He nods thoughtfully. “I’ll have to discuss this with Cathryn,” he says. Cathryn is the editor in chief. “I’ll let you know what she decides.”

“Okay,” I say, wiping my palms on my trousers once more and getting up. “Well, thank you. I appreciate it.” I nod to him and leave the room.

I file nervously, telling myself not to be nervous. The worst they can say is “no,” right? And why would they say that? I’m a nice person and I file well. I may be meek and boring, but certainly no one can say I am not nice. Prepare yourself for a long wait, I tell myself. Don’t expect them to get back to you today. And probably not tomorrow either. It may take a week before they give you their answer. They may even forget. I’ll have to remind them, if they haven’t gotten back to me in a week.

Time flies more quickly than usual. About two hours later, Annie comes to me and says, “He can see you in his office now.”

“Oh, okay,” I answer, dazed.

She follows me into the office and again arranges the books on the shelves.

I sit across from my boss.

“I just spoke with Cathryn,” he says, “and after some deliberation, we both agreed that your services are no longer needed.”

“What do you mean?”

“We would appreciate getting your resignation tomorrow morning, if that is convenient for you.”

“I’m willing to keep on filing.”

“That is not convenient for us. We would prefer to get your resignation. We would be grateful.”

“Why? What made you decide this?”

“My talk with Cathryn. We discussed your proposal and came to the conclusion that actually we do not need you for filing any more than we need you for fact checking.” He stares at me blankly.

I glance at Annie, hoping to get a look of sympathy from her, but her back is turned to me.

I go home. I was assertive, and look what happened. How much worse can things get? Bastard elephant.

Maybe it’s for the best. I’ll look for a new job, which will probably be better than the old one. Most jobs would be. But first I’ll take a break. A week or two, before I start sending out resume. Just enough time to take hold of myself and get my life in order.

Notice I’m speaking of my elephant as one would of God. “Maybe it’s for the best” is the excuse one gives when God goofs.

When Charlotte gets home from work, she sees her belongings in the hallway, tries to open my door, can’t, starts ringing, shouting, banging, calling, insulting, crying, kicking, threatening suicide, threatening to call the police, to turn me in, and finally falls silent. I look through the peephole. Her things are still there, but she isn’t. I open my door an inch, and she jumps up and flings herself against it. I was prepared for that trick, so I am not caught by surprise and am able to close the door easily.

The whole thing starts over: the bangs, the screams, the insults, the tears. I take a bath with earplugs in my ears. I let the hot water relax my muscles. A couple of minutes later I remove one earplug. She’s still banging.

“I got fired!” I shout to her from my bath.

The banging stops for a moment, but then it starts again.

“I don’t have a job, and I’m not going back to work,” I scream, hoping that this information will make her less eager to hold on to me. “Did you hear me?” I shout.

“Open the door,” she shouts back.

“Did you hear I got fired? Did you hear?” I scream at the top of my lungs.

“Yes, I heard, but you’ll get another job...”

I squish the earplug back in my ear and close my eyes, content. She heard. That’s all that matters.

I hear the phone ringing through my earplugs. I don’t answer it. In just three more days I’ll have peace from the phone, and maybe from my ex-girlfriend, and maybe from my cat, and even, if I’m lucky, from the strangers in the street, though I’m not getting my hopes up for that one.

The next morning I go to work carrying my resignation. I walk with my tail between my legs, my shoulders drooping. I’m a loser, a failure.

No I’m not. They are. Their lives are so empty and dull that they entertain themselves by performing petty cruelties. I must walk in there like a king. I must be the disdainful one, for once, the contemptuous one, the condescending one.

I march into the magazine, holding my head high, my nose stuck up in the air, and place my resignation on my boss’s desk. He’s out of his office. I certainly will not wait for him to return to say goodbye. As I walk toward the exit I pass Annie, sitting at her desk, and say, “Ciao, Annie. Happy filing.”

I take Minou to the vet and have her spayed. Two days later, she’s lying on my desk, looking at me blankly. I pet her head, but she’s as unfriendly as an ice pick. I try to pick her up, but she growls and stiffens, so I let her go. She settles back down, and I notice something orange peeping out from under her.

What is that? I ask.

Fuck off, she says, covering the orange object more completely with her body.

What is that thing? I repeat.

She turns her head away.

Don’t you dare scratch me, I say, sliding my hand under her.

She turns around ferociously and bites my hand. It bleeds. I shout. I feel an irresistible urge to grab her and fling her across the room, but I control myself because she has just had surgery.

You are a monster, I say.

You only said not to scratch, not not to bite, she answers smugly.

I pull the orange object out from under her. It’s the kitchen scissors.

What is this? I ask.

The kitchen scissors.

Did you drag these all the way here?

>

Yes.

You shouldn’t drag heavy things after your operation. What are they for?

To cut your balls off.

Since yesterday my mother hasn’t been able to call me because of my change in phone number. Charlotte is finally leaving me alone, Minou is getting nicer, but people are still coming up to me in the street and talking to me about little girls. I call my mother and ask her to stop sending her employees over. She refuses.

I see more of Laura and less of Lady Henrietta, because recently things have changed. Sara is not as nice as before, and she has health problems. She gets severe headaches and often throws up. This makes her moody and spoiled and affects her mother. Lady Henrietta invites me very rarely these days, and when I do visit, she never seems pleased to see me. I feel concerned for Sara, but I guess she has a stubborn flu and needs to be left alone with her mother.

* * *

I am pleased to announce that Laura is officially my girlfriend and I’m her boyfriend. It’s been the case since the first night, in fact, but I’m mentioning it now in case it wasn’t clear. We are very good for each other. She makes me more normal, and I make her less normal. I’ve told her about sleeping with my elephant. She took it well.

She also took it well when I “quit” my job. Although she works only for the respectability, not for the money, working is not something she requires of others. She’s extremely well balanced. People who are very well balanced don’t need ambition to be happy. They don’t need goals. They appreciate life. They live one day at a time and love each day. She evokes this same serenity in me.

Laura is tallish, but not extremely tall for a woman, which is good because I’m not very tall for a man. She is perfectly proportioned, and she’s as beautiful as a magazine model, her body too. She has light-brown hair and warm brown eyes. She’s a brown person: brown as in brown haireyes. Very sensible, but sensitive; down-to-earth, but warm; moderate, but able to be extravagant. In addition to being a brown person, she happens to be so gorgeous physically, mentally, and emotionally that any man would marry her instantly if he were lucky enough to be the object of her love, like I am.

Her face always glows with health, and her cheeks are pink. She has healthy-looking teeth that are not too white: they are very real-looking and blend well with the color of her skin. One eye wanders out sometimes, but ever so slightly and imaginatively—I mean “rarely”—that I always think it’s my imagination. It gives her an air of reality, of being a human, alive, who will die, which humans do.

Her personality, as well, is brown. Brown as in earth, down to earth.

We spend most of our time together at her place, not at mine, because although I keep my apartment clean these days, hers is bigger, more comfortable, more luxurious, paid for by her parents. It’s a big, pale apartment with lots of light and few cumbersome objects, except for a shiny black piano. She does not play it well but loves to play, anyway, and likes the look of the instrument. She says she has always felt happy in a room with a piano. We sometimes toy with the idea of living together but decide to wait until the perfect moment, a time when it will happen naturally, almost without our thinking.

I go to practically every one of Laura’s shows, to be nice and because I love her. I privately feel sorry for her and wish I could help her. It makes me suffer to see someone make such a fool of herself. Especially someone I know. Especially someone I like.

I finally decide I cannot let her go on with her pathetic show without at least trying to shake her up a bit. So one Sunday afternoon, at her apartment, I introduce the subject by making a casual comment.

“You know, I was thinking, it might not be a bad idea to show the empty boot first, before you take the flower out of it.”

“My foot’s in it. Isn’t that enough proof the boot is empty?” she asks.

“Of course not,” I say gently. “You know, I was wondering: you never told me if you know how to do any traditional magic tricks.”

“You don’t like my show,” she states flatly.

“Yes I do! I just thought it might perk it up a little to do some traditional magic, like when things seem to really disappear and stuff.”

“I don’t do that sort of thing. I do modern magic.”

“It seems more like baby magic to me,” I say. “Any kid can do it. No offense.”

“That’s what ignorant people say of abstract art. This is abstract magic, modern magic, postmodern magic, naive magic, experimental magic, avant-garde magic, an acquired taste. The dancing makes my work slightly more accessible and commercial. I could add singing, but that might overwhelm them.”

“To do modern stuff, you have to know the traditional stuff,” I tell her. “You can’t resort to modern stuff just because it’s easier. Good modern stuff is done out of choice, not out of inability to do anything else. Picasso was able to do extremely realistic portraits of people. He simply chose not to concentrate on that style.”

“I just don’t do realistic magic. It’s not my thing.”

“I know, but do you know how to do it?”

“Of course.”

“Could I see some of your tricks?” I feel like a policeman. Could I see your driver’s license?

She stares at me for a few long seconds and then goes into her bedroom to get her equipment.

She comes back and stands in front of me, holding a top hat and a wand. She proceeds to do the well-known, traditional magic trick, which one has seen a dozen times in the subways and on TV, of pulling a toy rabbit out of a top hat, after having shown me the empty hat first. She does it stiffly and clumsily. She truly has no talent for it. Not very coordinated.

“Pretty good, pretty good,” I tell her. “I wouldn’t compare you to Picasso, but pretty good. Can’t you do anything better than that, though?”

She makes an ugly face at me and does the well-known trick with the silver loops, of attaching them and detaching them, when they seem unattachable and undetachable. The tip of her tongue is stuck out in concentration. Truly nothing impressive, it’s almost worse than the baby magic she does onstage. You need a minimum of grace and assurance.

“Isn’t there any trick you can do well?” I ask, in a joking tone. I don’t want to seem too harsh, but I don’t want to be too soft either, or it won’t help her.

“You are ruffling my feathers, Mr. Acidophilus.” She really is offended. It’s nice she can joke about it and put on a light air. Perhaps I poked at a sensitive spot of hers. Perhaps she has a terrible complex about being incompetent at magic.

But she calmly proceeds to do the trick of making a card disappear under a handkerchief. She moves like a robot. She does it so badly that I can almost guess where she hid the card: in the lining of the handkerchief, or in her sleeve, or wherever cards are hid.

“Don’t you do anything well?” I ask.

She angrily slaps a coin into her palm, and it disappears before my very eyes, while her hand remains open.

“There, that’s more my territory,” she mumbles.

I look up at her face. She quickly looks away and repeats the traditional trick with the silver loops. I stop her.

“Laura, that thing you just did. What was it?”

She blushes, pouts, looks distressed, and quickly blurts out, “You just pushed me too far. You humiliated me. I wasn’t thinking. Let’s erase the slate. I want to lose consciousness.”

“I’m sure you do,” I say, stunned. “I’m sure you do,” I repeat involuntarily. “That seemed mighty much like real magic to me.”

“Of course not. That’s the only trick I’m good at. I just happen to do it well because it requires no sleight of hand.”

“It requires no sleight of hand? Then it sounds even more like real magic to me.”

“Well, it’s not.”

“Then show me how you did it.”

“It’s too complicated to explain.”

“Try.”

“No. Magicians are absolutely never supposed to reveal their tricks,

no matter what. But you can go to any magic store and buy the kit with the instruction book.”

I do exactly that. Early the next day, I go to a magic store and ask for a trick that enables you to make a coin disappear while your hand is open. They do not sell such a thing, of course, because such a trick can be performed only by fairies or witches or TVs. When I get home, I tell her I didn’t find her trick for sale.

“Yeah, well, I didn’t think you’d go check,” she says. “I just wanted to get you off my back. It was actually my grandfather who taught it to me.”

“I don’t believe you for one second, just for the record.”

“The only reason you’re obsessed with it is because it involves a coin, like when you were little,” she says. “If it had been a button in my hand, or a thimble, or a ring, or a pebble, you wouldn’t have given it another thought.”

“Not true.”

“Yes true.”

“Not not not.”

“Yeah yeah yeah.”

“No, I tell you.”

“Yes, absolutely.”

“Not on your life.”

“Yes on my life.”

“Forget it,” I say, waving my hand. But I then turn toward her eagerly and exclaim, “Do it again!”

“Never. Drop your fixation.”

“Never.”

We stare at each other, almost panting. I suddenly plop down 0n the couch, exhausted. “I understand your dilemma,” I drawl. “You’re obviously not good at traditional magic, and it would he too risky for you to do your real magic, because even if you tried to make it look like fake magic, there’s always the chance you could get discovered. So all you can do is your postmodern baby magic. I understand your problem, and I now respect your decision.” I close my eyes. My case is closed: There is nothing you can say that will make my words untrue.

“Oh, please! Give me a break,” she says. “My real magic? Yeah, right, Jeremy.”

Nude Men

Nude Men